A study from the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health has found that pregnant women exposed to high levels of ultrafine particles from jet airplane exhaust are 14% more likely to have a preterm birth than those exposed to lower levels.

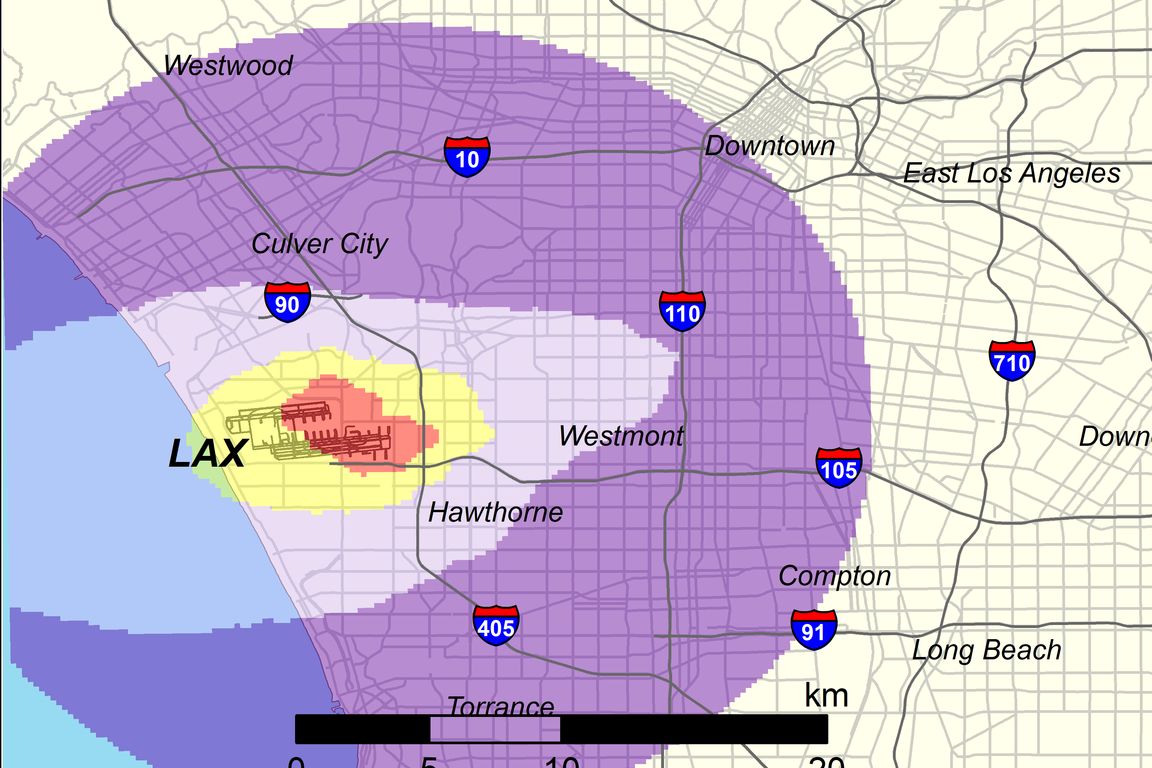

The researchers examined exposure among women living near Los Angeles International Airport, in an area that includes neighborhoods in Los Angeles, El Segundo, Hawthorne, Inglewood and several other communities inland from the airport.

“The data suggest that airplane pollution contributes to preterm births above and beyond the main source of air pollution in this area, which is traffic,” said Dr. Beate Ritz, a professor in the departments of epidemiology and environmental health sciences at the Fielding School.

Preterm birth is associated with complications such as immature lungs, difficulty regulating body temperature, poor feeding and slow weight gain.

The research team, co-led by Ritz and Scott Fruin of the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, examined records for all births — a total of 174,186 —between 2008 and 2016 to mothers living within 9 miles (15 km) of LAX. They divided the overall area into four sections based on the amount of ultrafine particle, or UFP, pollution from jet exhaust, with the section nearest the airport experiencing the highest exposure.

After adjusting for traffic-related air pollution and other variables that may affect the risk of preterm birth, including airport-related noise and the mother’s age, education level and race, they found that expectant mothers in the quarter with the highest average ultrafine particle exposure had 14% higher odds of a preterm birth than mothers in the quarter with the lowest exposure.

“Nearly 2 million people live within a 10–mile radius of LAX, many of whom are exposed to elevated levels of aircraft-origin UFPs,” said Sam Wing, a scholar at the Fielding School who also worked on the study.

The research is summarized in an article published July 22 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives and is based on a lengthy study from the spring 2020 edition of the journal. Other authors include Timothy Larson and Sarunporn Boonyarattaphan of the University of Washington and Neelakshi Hudda of Tufts University.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Leucine is a BCAA that has been proven to enhance the

uptake of blood glucose by your muscles and thus lower

your blood glucose ranges. Yes, you probably can take BCAA on a Keto food regimen with out worries as BCAA does not have any carb

content material and this low-calorie supplement doesn’t create any notable rise in your insulin ranges.

BCAAs, as talked about within the above part, are recognized for their

capacity to boost vitality and endurance throughout a exercise (87, 88).

A powder complement in a straightforward to drink type is really helpful at this time as this is absorbed a lot sooner than a

BCAA capsule. Cortisol (stress hormone), released due to the bodily exertion of

operating, could cause muscle breakdown and eventually leads to weakness

in leg muscles. Researchers have noticed that the actual limiting issue that inhibits human performance is our mind,

not our muscle tissue. We are inclined to slow down when our mind indicators to our muscles that they are tired, even once we

are bodily capable of continuing.

It is a compelling option for these in search of substantial features with peace of thoughts concerning well being

and legality. These capsules are additionally manufactured in a facility that is compliant with current good

manufacturing practices (CGMP). Meals and Drug Administration (FDA), ensuring that the complement is consistently

produced based on high-quality standards.

All BulkSupplements merchandise are manufactured on the highest quality based on cGMP requirements, as well as third-party tested to make sure consistency and requirements.

In this publish, we researched the most effective BCAA dietary supplements in the marketplace, explained how they work, and the essential components to

look out for whereas shopping for them online. Bear

In Mind, what works finest for you is a extremely particular person matter, based

mostly in your physique, your objectives, and your private preferences.

Now, if you’re somebody who tends to go all out at

the health club, those intra-workout BCAAs may be your friend.

For optimum outcomes, you’re advised to take a minimal of 2

servings of this BCAA powder. Normally, prospects that have

purchased the product will depart sincere evaluations and give you a good idea of the quality of the supplement.

We advocate testing review blog pages (like ours),

product sites, Reddit, and YouTube to find more evaluations of the

BCAA complement you’re trying to buy. It is value noting that purchasing protein powders that embody BCAAs will usually run higher than the worth vary acknowledged

above. Some of those distinctive flavors include Swedish Fish and Bitter Patch Youngsters Blue Raspberry, Redberry, and Watermelon.

Invigorate your body with clear power through VitaMonk’s Clear EAAs complement formula.

L-Taurine and coconut water blend help with blood circulate, restoration, and

muscle gains. If all-day vitality manufacturing is what you’re

missing from a supplement, Primeval Labs EAA Max is value a shot.

The finest EAA aminos with a boost of hydration means your body will be working at its max potential to extend your

endurance, refuel, and recuperate sooner. If you’re on the lookout for a tasty BCAA complement to offer you a

boost of motivation pre-workout, look no additional than our bestselling BCAA Powder.

Research have noticed that those who devour BCAA supplements after resistance

workouts had increased protein muscle synthesis compared to those who did not (12).

For a few years, the advantages of BCAAs have been touted by train nutritionists.

And whereas these claims are still legitimate, more and more analysis is coming out that reveals

the importance of essential amino acid (EAA) supplementation. The benefits of Clear Labs

BCAA Glutamine include sooner restoration instances, improved efficiency and elevated focus and power.

BCAA vitality drinks is normally a helpful addition to any athlete or health fanatic’s training

regimen. They might help to support muscle recovery and

progress, cut back muscle soreness and fatigue, and provide an vitality

increase. BCAA power drinks are a kind of sports activities drink that include branched-chain amino acids

(BCAAs), which are a gaggle of important amino acids which are crucial for muscle restoration and

development.

In Accordance to specialists within the vitamin area, one of the best time to take BCAAs is minutes before and

during train. At the time of pre-workout, should you take BCAAs together with pre-workout

drinks, they may energize your muscle tissue, promoting the cells to draw vitality from blood sugar, not from the liver and muscle.

Due To This Fact, supplementing with BCAAs at this time prevents catabolism

and muscle loss whereas sustaining train efficiency.

BCAAs assist with muscle synthesis, so you can expect to be taking a lot when you

are gaining mass. Fortuitously, the ultra-pure powder-form

BCAAs from BulkSupplements are simple to incorporate into

your mass gainer or protein shake of alternative for accelerated muscle mass features.

A meta-analysis of studies printed in Nutrients concluded that supplementing with BCAA helps prevent muscle injury

and relieve soreness in males after resistance exercise [4].

Should you enrich your food plan with BCAA, or should you consider taking a complement earlier than, during,

or after exercise? Let’s have a glance at what the evidence

has to say concerning the potential BCAA benefits for optimizing performance and different

health parameters. The info provided in this information is for academic purposes only and shouldn’t replace skilled medical

recommendation. At All Times consult with a healthcare skilled earlier than starting any new dietary supplement or exercise program.

This supplement is clear, but it also has a wonderful taste that

helps make taking it extra enjoyable. Naked BCAAs is a vegan supplement possibility that is non-GMO and soy-free.

With 5 grams of BCAAs per serving, this complement has zero carbs and

calories.

Powder supplements tend to be absorbed quicker as they’re available.

The outer covering of the capsules has to dissolve first earlier than releasing their contents, thus slowing down their absorption. On the other hand, BCAA powder dietary supplements have customizable dosages and you’ll take as little and as a lot as required, relying on the size and intensity of your

exercise. BCAA dietary supplements can be found out there in the form of pills and powder.

Overall we expect that Big Aminos is one of the best BCAA supplement available on the market as a result of

its premium ingredients, clinical doses of branched-chain amino acids, and inclusion of coconut water powder.

It is the BCAA complement choice that we imagine would work for the vast

majority of lifters looking to enhance muscle growth and reduce muscle fatigue.

BCAAs are related to muscle constructing via one amino acid, leucine.

Leucine is known to activate one of many cell pathways that

leads to muscle growth. Nonetheless, we want all the essential amino acids, not just the BCAAs, to spice up protein synthesis and

muscle growth. Subsequently, BCAAs may not be the best way to stimulate muscle-building

processes.

It can also assist your physique increase protein synthesis

with a few of the industry’s best amino acid combos. Alpha

Amino is a performance-enhancing BCAA supplement powder with 30 servings per container and is one

of the finest amino acid dietary supplements. Taking AminoLean will have an effect on your power levels,

providing you with the required enhance that you need earlier than a workout.

Leonard Shemtob is President of Robust Dietary Supplements and a

published creator. Leonard has been within the supplement space for over 20 years, specializing in fitness dietary supplements and nutrition. Leonard appears on many podcasts, written over

one hundred articles about dietary supplements and has studied

nutrition, supplementation and bodybuilding.

If you might be coaching late and are delicate to caffeine, our BCAA Amino is

also the greatest option. For most people, although, the best advantages of BCAAs are their capability to forestall muscle harm, boost muscle recovery, and help with muscle strength and muscle mass features.

Taking a BCAA supplement earlier than or after your gym session is a great way to take benefit of these advantages.

These days plenty of amino acid dietary

supplements are available in a variety of flavors.

This may be overcome by mixing the product with juice or a sports drink, which can mask the flavor.

Alternatively, Bare Nutrition also has comparable BCAA merchandise in Cherry Lime or Strawberry

Lemonade flavors. We also liked that this complement is vegan, in addition to soy and gluten-free, making it appropriate for a broad variety of individuals.

Just like the timing of your BCAA dietary supplements, your BCAA dosage additionally is dependent

upon your personal objectives and wishes. Liver cirrhosis

also increases the danger of hepatocellular carcinoma,

a type of liver most cancers (29). Researchers have noted that BCAA supplements could cut back the most cancers danger in those with liver cirrhosis (30, 31).

The greatest time to take EAA is intra exercise, or while you exercise, and after your exercise.

Athletic Perception Sports Activities Psychology and Train Group was established in 1999,

serving as a hub for sports psychology, exercise, and dieting.

ON Instantized BCAA comes in three primary flavors, though the most popular unflavored choice.

If taken earlier than a exercise, they will additionally function a further energy supply in your muscular tissues after glucose depletion. NOCCO BCAA

Energy Drink Caribbean Pineapple is a ready-to-drink beverage with BCAAs, amino acids, and nutritional vitamins B6 and B12.

This clear vitality drink is sugar free, low calorie, and incorporates 180mg of caffeine.

Prospects love the refreshing Caribbean Pineapple taste and the enhance of vitality it supplies.

Adding a dose of BCAA to your workout might help improve

your muscle energy, lower fatigue and muscle breakdown,

and higher your recovery.

BCAAs complement protein aids, creatine, citrulline

malate, ß alanine and vitamin B products. Consuming

a whey or vegan protein after the workout with 5-10 grams of

BCAA is essential to maximise muscle gain. They additionally enhance power and muscle mass when used along side creatine.

For exercise enhancement, the best time to take BCAA is before, after,

and through exercise on workout days and in the morning and night on relaxation days.

However, you can also divide up the dosage all through the

day often instead to spice up muscle growth. BCAAs help liver health and may help regenerate

cells in the organ. If you aren’t getting sufficient amino acids frequently, you can expertise

problems with muscle development.

If you need to discover a complement that is compatible with you, this is a consideration to

make. If you don’t want any flavor at all, there are plenty of these supplements that are out there in capsule

type. This is a giant consider determining simply how appropriate

a sure product might be along with your needs and preferences.

It doesn’t matter whether you need to achieve power, shed pounds, construct muscle, or improve stamina and endurance.

Correct supplementation is the key, and the effectiveness

of supplements is decided by their purity and high quality.

As discussed above, whereas each are great dietary supplements, BCAAs assist protect muscle and aid

in restoration, whereas creatine will increase your body’s energy

manufacturing during high-intensity efforts.

As An Alternative, they source their vegan amino

acids from high-quality InstAminos developed via fermentation. Department chain amino acid dietary supplements are

bought in either capsule form or powder kind. BCAA users maximize their muscle achieve as

this supplement helps to prevent muscle protein breakdown during

intense weightlifting classes.

References:

https://www.garagesale.es/author/clementp139/

https://cascaderpark.pl/how-to-hydrate-skin-like-a-pro-according-to-dermatologists/

https://www.selfhackathon.com/when-to-start-post-cycle-therapy/

http://forums.cgb.designknights.com/member.php?action=profile&uid=16675

https://vivainmueble.com/index.php?page=user&action=pub_profile&id=44263

https://www.selfhackathon.com/does-gua-sha-really-work-to-minimize-a-double-chin/

https://utahsyardsale.com/author/chadwick32p/

https://body-positivity.org/groups/the-6-strongest-oral-steroids-and-their-risks/

http://forums.cgb.designknights.com/member.php?action=profile&uid=16587

http://graskopprimary.co.za/fake-and-real-steroids-know-the-difference/

https://eskortbayantr.net/author/porfiriojqh/

https://www.murraybridge4wdclub.org.au/forums/users/sommerholte6/

http://www.annunciogratis.net/author/mahalia7407

https://pet.fish/community/profile/shanonhutchinso/

http://www.forwardmotiontx.com/2025/03/06/post-cycle-therapy-pct-in-bodybuilding-a-comprehensive-guide/

https://www.smfsimple.com/ultimateportaldemo/index.php?action=profile;u=867108

harley davidson true dual exhaust system https://otvetnow.ru site host